Consumer news, tips, commentary and musings by veteran consumer and personal finance journalist Anthony Giorgianni

Contact me at anthonyconsumer@gmail.com

Also on Blogger

Find my previous posts below :

Visit page 2 for these posts:

Nine post-holiday tips for gift givers and recipients

Register gift cards, fill out warranty registration forms, handle returns promptly and more

12/28/18

The holiday gift-giving season is coming to an end, but it may be just the beginning for some gift-related tasks. Here are nine post-holiday chores you might need to do, whether you're a gift giver or recipients.

Don't put off returns. If you're planning to return a gift, make sure you carefully follow the merchant’s return policy. You may have just 30 days or less to bring or send an item back for an exchange or refund. With many retailers, the return period for some products, such as electronics, may be shorter than for the other merchandise they sell. And if you need to exchange a seasonal item, such as clothing that's the wrong color or size, supplies may be limited.

Also keep in mind that some stores may not accept the return of items that have been opened. Even if they do, you’ll likely need the original packaging. So if there’s a chance something may need to go back, don't just start using it, and keep the box or other packaging it came in.

Fight for your rights. For gifts that arrive broken, have missing parts, or have been misrepresented, the gift giver should contact the retailer immediately. Unless the gift was sold as-is (which isn't allowed in a handful of states), it doesn't matter what a store's return policy is. Customers have a right to get what paid for. If you shopped online or by phone, it's your right to reject an item that arrived later than the seller promised or after 30 days if no promise was made. In fact, the law requires sellers to issue a refund automatically when such delays occur. If the retailer refuses to make things right, the gift giver should seek a charge-back from his or her credit card issuer. (Hopefully, a credit card was used for the purchase.)

The product manufacturer also may help resolve an issue, especially if it's warranty-related or a involves a missing part. But don't feel like you must deal with the manufacturer, even if the package contains a notice instructing you not to return the product to the retailer, as many seem to do these days. The fact is retailers are responsible for what they sell. And dealing with a retailer, especially if it's a local store, can be a lot easier than working things out with a manufacturer that's hundreds of miles away.

Check your credit card and bank statements. Make sure that your statements accurately reflect your gift purchases. Look for incorrect amounts, double billing and charges for things you didn't order or that you cancelled. If you see an error, contact the seller immediately. If the merchant refuses to correct the problem, or if there's fraud, let your credit card issuer or bank know immediately.

Request receipts. If may sound tacky, but you may need the receipt to return an item or make a warranty claim with the manufacturer months or even years from now. For non-receipt returns, a merchant may deny the return or give you a refund or store credit for the item’s most recent selling price, not necessarily the amount the gift giver paid. In addition to the regular receipt, many stores provide gift receipts, which don't display the item price. A gift receipt likely will entitle you to a store credit, not a refund. On the other hand, if you have the regular receipt, any refund may go back to your give-giver's credit card and not to you.

Return warranty registration cards. Under federal law, companies are allowed to require you to register the product as a condition for honoring a limited warranty. (That’s not permitted for full warranties, a relative rarity these days.) So return the card or provide the information on the manufacturer's website, if you're given that option. Another benefit to registering the product is that it can help the manufacturer contact you if there’s an issue with the product, such as a safety recall. Along with your name and contact information, some registration cards ask for details about the activities you engage in, your income and education levels and other personal details for use in marketing to you. You don't need to provide that.

Send in rebate requests. If you purchased gifts that include manufacturer or merchant rebates, submit the rebate form as soon as possible so you don't forget or miss the deadline. Rebates often require you to send the UPC code from the product packaging. If you don't have it, you'll need to request it from your gift recipient.. Hopefully, he or she still has the packaging; otherwise, you may be out of luck. Keep in mind that once you submit a rebate request, the retailer likely won't allow you or your gift recipient to bring back the item under its return policy.

Read and save product manuals. You probably can think of better things to do with your time. But it's important to read the manuals that came with your gifts, not only for information about how to set up and use the product, but for details on how to maintain it properly. Misusing a product or failing to perform the manufacturer's recommended maintenance could void the express warranty. And the manual may include important safety warnings. If you don't already have a good place to store your manuals, now is a good time to set one up. While you're at it, attach the receipt in case you need it later on.

Review and update your inventory and home insurance. You may need to add those gifts to your personal inventory in case you need to make a claim because of a fire, flood, theft or other loss. Also review your policy limits. If you received valuable gifts or purchased expensive items for members of your household, you may need to increase your coverage or, with certain items, such as pricey jewelry or art, purchase a floater policy to cover them specifically.

Use and register gift cards. If you received gift cards, plan to use them right away. Many cards can't be replaced if lost or stolen. And for those that can, issuers often require that you register the card or provide the original purchase receipt (another reason to request receipts.) Another concern, especially with retailer-issued cards, is that the store, restaurant, health club or other establishment might close locations or go belly-up, making its gfit cards difficult or impossible to use. (If an issuer goes bankrupt, cardholders usually end up with little or nothing from the bankruptcy proceedings.) And don't think you have nothing to worry about if you received a bank-issued gift or prepaid card, one with a major credit card logo. They typically have fees that can slowly diminish the card’s value.

It may not be easy, but it's time

to jettison all that debt and start saving

Should You Give Through Crowdfunding Websites?

Why You Should Consider having More than One Bank

Save Money By Doing Repairs Yourself

A $300 Oil Change For Your Car?

Think Twice Before Buying a Home Warranty

Buying a House? Choose a Home Inspector Carefully

Visit page 3 for these posts:

2/15/19

A new Bankrate survey that examines how much people have in credit card debt compared to emergency savings raises in interesting question: How much should you keep in an emergency fund if you also owe money on your credit cards? My answer is: very little, if anything.

The Bankrate survey of 1,004 consumers revealed that three in every 10 Americans have more credit card debt than emergency savings.

Of course, having any credit card debt is reason to worry. And too many people are living paycheck to paycheck, a problem underscored by the recent federal shutdown.

But what if the survey found the opposite, that people have more in savings than credit card debt? That's actually worse. It would man that they are keeping money in a savings accounts earning, say, just 2.5 percent while paying double-digit interest on their credit cards. That makes no sense.

Think of it this way: Would you borrow money at, say, 22 percent interest so you can put it in the bank at a 2.5 percent? Of course not. But that's essentially what you're doing if you're stashing money into an emergency fund while also paying credit card debt. Having an emergency nest egg might make you feel better, but the cost is way too high.

Consider this example. Suppose, despite your credit card debt, you try to follow the advice of financial gurus and create an emergency fund equal to eight months of living expenses. If the monthly expenses for your family of four total $5,000, your emergency fund would need to have $40,000. If you tried accumulate that much in 12 months, you'd have to sock away more than $3,300 a month. To achieve that over three years, you'd be putting away $1,100 a month. But if you had that kind of money to put into savings consistently, month after month, you probably wouldn't have credit card debt to start with, or you would have seriously mismanaged your finances.

Even if you got a sudden surge in your monthly income or inherited a big chunk of cash, does it really make sense having tens of thousands of dollars in an emergency fund while you're getting killed paying credit card interest? The fact is, if you have credit card debt, that is an emergency that you need to address ASAP. Not only are you likely paying high interest, but when you carry a balance on a credit card, you lose the interest-free grace period of 30 days or so, which means having to pay interest on every purchase you make from day one!

On the other hand, if you use every bit of spare cash to pay off your debt and an unexpected high-cost emergency arises, such as a major car or home repair, you always can, as a last resort, use your credit card to pay for it, assuming you haven't maxed out your credit. Yes, that's not an ideal solution. But if you're keeping a higher credit card balance so that you can fund an emergency savings account, you're essentially borrowing as a hedge against an emergency that may not even happen.

Of course, the main point of the Bankrate study is to demonstrate that we're a society in crisis financially. A 2017 study (pdf) commissioned by the Federal Reserve found that four in 10 adults couldn't handle a $400 emergency expense without having to borrow money or sell something. That's scary. But the main take away from all this is not that people have more debt than savings; it's that they're charging more than they can pay off in a single month, period.

The Bankrate survey suggests that things are only getting worse, which is hard to understand given the improving economy and low unemployment rate. It could be that consumers, more confident in how they're doing financially, are willing to take on more high-interest debt and the risk it involves, which is exactly the wrong approach! If you're in good shape financially, now is the time to get your financial house in order and to keep it that way.

What to do

Throw every extra penny you have at your high-interest debt. Make a budget that can serve as road map for getting yourself debt-free (more on that later). One exception is if you've maxed out your credit and wouldn't have any way of covering an emergency. Then it might make sense to maintain some money in savings. But use your judgment. Those credit cards are costing you far more than you could ever hope to earn in a savings account.

Why You Shouldn't Keep Emergency Savings If You Have Credit Card Debt

An emergency savings fund may make you feel better, but it's way too costly

Federal Shutdown Underscores Danger Of Living Paycheck to Paycheck

Ten Dos and Don'ts For Holiday Gift Giving

Consider Carefully

Before Accepting Store

Deferred Interest Financing

Saving on Cable: It's a Crazy Game, But You Have to Play It

Freezing and Unfreezing Your Credit File is

Now Free Nationwide

Consumer Fraud:

The Storm After the Hurricane

1/14/19

There has been a lot of news coverage about the negative effects the government shutdown is having on workers and others who depend on receiving federal dollars.

I've seen reports about government workers, contractors and others who, if the shutdown drags on much longer, won't be able to make their rent or mortgage payments, pay medical bills and utilities or even afford food.

This has me thinking. How did we get to the point where so many people are living from paycheck to paycheck? Whatever happened to saving accounts and other investments that people can depend on during financial emergencies?

This is not to say that the federal shutdown is fair or a good thing or that people who don't have substantial savings deserve whatever they get. But there are many unexpected events that happen in life that can stress us financially. It could be a job loss, illness, unanticipated major repair of your home or car, among other things. The fact is a large number of Americans are simply unprepared even for little emergencies, let alone the big ones.

This is hard to believe: Of the more than 12,000 people who responded to a Federal Reserve-commissioned survey (pdf) in late 2017, only half said they have enough savings to cover just three months of expenses if they lost their jobs. And only 59 percent said they could handle an unexpected expense of just $400 by paying cash, using their savings or putting the expense on a credit card that they could pay off in just one month. Most of the others said they'd be forced to charge the amount to a credit card and pay it off over time or borrow the money from friends and relatives.

So what's going on and what can be done about it?

It's important to acknowledge that for many people with low incomes, just covering basic expenses makes it difficult or impossible to put any money aside. (That's a subject for different blog post.) But for many others, it's an issue of accumulated debt. Just making their loan payments, in addition to coping with other everyday expenses, leaves nothing at the end of the month to save. Even if there is money left over, it doesn't make sense to save money at, say, one or two percent interest while paying much higher rates on the amount that's still owed. So one's bank account remains empty, and the only choice in an emergency often is to borrow even more. Yikes!

It's one thing if this was caused by a major event that's out of one's control, such as an illness that wiped out the family savings. But it's entirely different if it has been self-imposed by years of spending more than one earns or has saved.

Falling into the trap

And it's easy getting snared by this trap. When it comes to those finer things in life, companies make it hard to say no, offering many inducements for people to take on debt as a mechanism for getting want they want. Consider, for example, car leases and long-term loans, which are designed to get consumers to focus on the monthly payments instead of the overall cost. Suddenly you actually can get that new car or high-end model you thought was out of reach. Or how about merchant deferred interest offers, which let you buy today and pay tomorrow, often with no interest. With some of these deals, you don't even have to make any payments until the due date. (Just don't miss a payment or pay late. If you do, you'll suddenly find yourself owing all that deferred interest, which can accumulate at double-digit rates.)

Of course, there also are those ubiquitous credit cards, which put mostly everything in reach, even if it costs more than you can pay at one time. And, really, who wants to wait for stuff, even products and services that aren't a necessity, when you can get them now? Why shouldn't you be driving a Lexus when your brother-in-law is? Doesn't your family deserve a swimming pool as much as much the neighbors do?

That attitude is exactly what companies are counting on. Despite the touchy-feely, warmhearted impression you might get from their commercials, companies don't care about you. What they're interested in is selling as many widgets as possible to ensure that their major shareholders executives or both can afford a big white house with a helicopter landing pad. And it doesn't matter to them that you're going into debt, as long as you're able to pay, even if means cutting back on food or heat, or spending the kids' college fund.

And companies aren't the only ones responsible. The very nature of our economy makes it difficult even for those with middle-class incomes to get ahead without struggling. It's an unfortunate reality that supply and demand keeps prices generally just below the point where middle class wage earners say enough is enough. That's because if people are willing and able to pay more, the market will be all too happy to accommodate them.

Making matters worse is the emergence of dual-income households, which allows people to bid up prices even higher, to the consternation of those with only a single household income. (Earlier today, I saw a furloughed federal worker on CNN complaining about that very thing.) Beyond that is consumers' willingness to assume as much debt as they can get away with, which drives prices even higher.

As a result of all this, we're at a point where so many people feel they have to live on the edge. So when the government shuts down, workers are laid off, or any other emergency disturbs the precariously balanced normal, it's crisis time. And for those with low incomes, it's pretty much crisis time all the time.

What To Do

It's important periodically to reflect on the fact that borrowing money doesn't create wealth. Instead, you're essentially spending your future earnings today, along with having to pay interest for the privilege. If your income already is insufficient to let you live comfortably with a healthy financial nest egg, adding or increasing your future debt payments isn't going to make life easier. Of course, you might get a higher paying job or otherwise be in a better position to handle those future higher expenses. But can you really count on it, or are you just hoping?

Face it, if you're not paying your credit cards off every month, if you haven't saved at least six months of living expenses (at least a year is better), you're in a financial crisis that you must address. That means taking yourself out of that losing game that so many people are playing these days.

The first thing is to get a good idea of your income and expenses and see where you stand. And then set up a realistic budget that has you spending less than you make, allowing you to pay off your credit cards and other short-term debt and, once you've done that, accumulate savings. It's not as complicated or tedious as it may sound.

Despite what you may have seen elsewhere, you don't need to create a granular budget that focuses on things like pet supplies, entertainment, and dining out. You just need to make sure that you can cover your recurring and essential expenses, pay off your debt or add to your savings, and, hopefully, have enough left over to have fun. I'll be providing a simple approach to budgeting in another blog soon. But given that it's January, now is the perfect time to get started. All you need is a simple spreadsheet program such as Microsoft Excel or the Calc application in the wonderful and free Apache OpenOffice suite.

Also, be careful about long-term debt commitments. They can leave you vulnerable during financial emergencies, not to mention sticking you with high finance charges.

Of course, you'll likely need a mortgage if you're buying a home. But must you really go for the highest amount the bank will lend you? If you can't otherwise afford the kind of house you really want, perhaps a better approach would be to wait while you save for a higher down payment or increase your income. And when you take on that mortgage, be sure you have enough to cover the payments for the next six months to a year if you lose your household income because of a layoff or other emergency.

Car loans and leases also are tricky. Preferably, you'll have enough savings to buy a car with cash. (Yes, I really said that!) Unless you're getting zero percent or super low-interest financing, it makes no sense to borrow money for a car while you're keeping savings at one or two percent or in risky investments. If you must borrow, follow the old 20/4/10 rule. That means putting at least 20 percent down, keeping the loan term to no more than four years and making sure your vehicles expenses – including the loan payments – are less than ten percent of your monthly gross income.

The problem with car leasing is that it's deceptively expensive. It's true that the monthly payments are much lower than they would be for an equivalent loan. But you'll pay for that benefit with the hidden interest charges, which typically are much higher, especially now that interest rates are rising. And leasing puts you on track to get a new vehicle every three years or so. That sounds great. But given that new car and trucks lose their value much more quickly than older ones, repeatedly leasing has you constantly paying exorbitant new-car depreciation. And while those payments might comfortably fit into your budget, you'll end up with what amounts to life-long car payments. And just try to get out of that lease if you lose your job or have any other financial emergency or even if you die! It likely will be very expensive. I'll reveal more about the hidden dangers of leasing in a future blog.

In summary, you and your family should do everything possible to avoid living on a financial cliff, as difficult as that may be. If you're already there, now is the time to figure out how to fix it. It takes planning and self-control. But once you're debt-free and have a fat savings or investment account that both insulates you from life's little emergencies and leaves enough for the finer things, you'll feel great. And when you decide it's time to buy that new car or take that big family vacation, you'll be able to do it without having to worry or feel guilt – and with no risk.

Good luck and stay tuned.

SPECIAL REPORT: Car Leasing Is Much More Expensive Than You Think

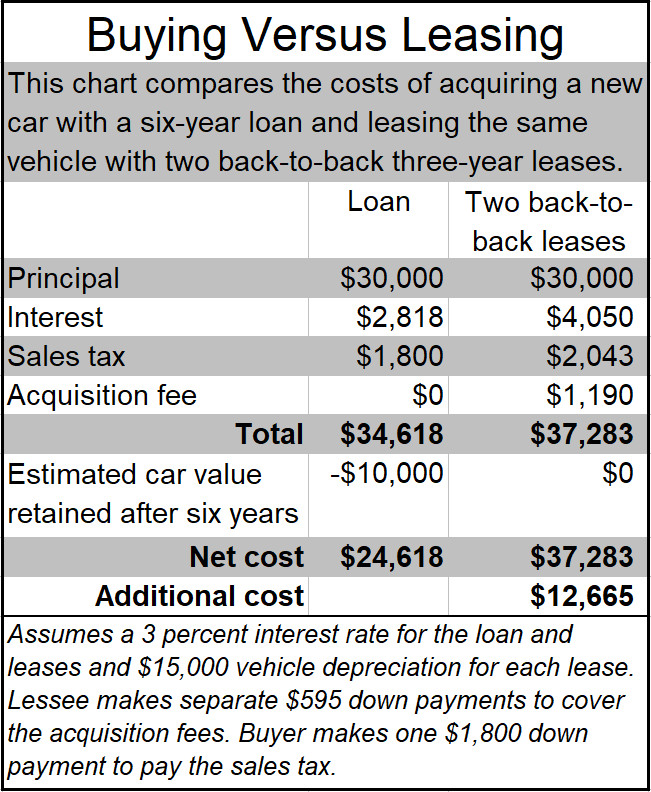

Just two back-to-back leases likely will have you paying thousands more than buying and holding the car for the long term

3/10/19

If you're like a lot of drivers these days, you're leasing a new car every few years.

And it seems to make perfect sense. You're always driving a shiny new ride equipped with the latest technology, and the payments are about half what they'd be with a three-year loan. Plus, your vehicle always is covered by the manufacturer's bumper-to-bumper warranty.

So, what's not to like? Nothing, if you don't mind paying thousands of dollars more than if you simply bought the car and held onto it for the long term.

The reality is that leasing, with its low monthly payments, is a deceptively expensive way of acquiring a vehicle, especially if you lease repeatedly. And the cost will only get higher as interest rates rise. Yet, leasing remains popular. Currently, about a third of new vehicles are leased, often by those who already are financially stressed.

This story explains what's really going on under the hood when it comes to leItasing. It includes a lease-versus-buy comparison that likely will shock you.

Understanding leasing

First, a quick leasing overview. Leasing is an alternative way of financing a car. For example, whether you lease a $30,000 car or take out a loan to buy it, you're borrowing $30,000 (assuming no down payment), and you'll be charged interest on that entire amount minus whatever you pay back along the way.

And that's the difference between leasing and buying: The amount you pay back. With a loan, you'll pay back the entire $30,000. But with a lease, you'll pay only the so-called depreciation, the vehicle's loss in value while you're driving it. Over a three-year lease, that might come to around $15,000, half as much as you'd pay with a loan. And that's why those lease payments are so much lower, and it's why many people lease again and again. But unlike with a loan, you won't own the car at the end of a lease. Instead, you'll return the vehicle, now worth the remaining $15,000 (the so-called residual value), unless you decide to buy it.

If this were all there was to it, the net cost of leasing and buying should be equal. The lease would cost $15,000. The loan would cost $30,000, but you'd end up owning a vehicle worth $15,000 at the end, for a net cost of $15,000.

But there's more to consider, among them those pesky finance charges. Because you're paying back less with a lease, that leaves a greater unpaid balance subject to a finance charge month after month. For example, the monthly balance for a lease on that $30,000 car is $22,500. At a three percent interest rate, the average monthly balance for a loan is about $15,700. As a result, with a lease, you'd be paying interest on an average of nearly $7,000 more every month.

But the biggest financial issue with leasing is that it puts you on track to get a new car every few years. That may sound great, but it's really expensive. That's because cars lose their value the fastest when they're new. In fact, a new car can depreciate 20 percent during just the first year. So, if you keep leasing, you'll end up on a new car merry-go-round, in which you're constantly paying that super costly depreciation. Compared to buying and holding onto the car for the long term, you'd be paying thousands of dollars more, as I'll show you in a moment. Of course, that same problem occurs if you buy a new car every three years, too. But with a lease, you're forced to take action every time the lease ends; and for a lot of people, the temptation to lease yet another new vehicle is too much to resist.

Beyond that, leasing has extra costs you don't won't have to pay if you buy, such as the so-called acquisition fee, which these days ranges from around $600 to $1,000 every time you lease. More on that later.

Lease vs. buy

So, let's look at a lease versus buy comparison.

First, it's important to understand that for most people considering a three-year lease, the alternative is not a three-year loan, which would have monthly payments about twice as high as the lease. Instead, the alternative is a six-year loan, which would have about the same monthly payments.

That's why, for our comparison, we'll look at two motorists, one who opts for two back-to-back three-year leases on a $30,000 car and another who takes out a six-year loan for the same vehicle. We'll assume the car has an average three-year depreciation of $15,000, and we'll use a manufacturer-subsidized three percent interest rate for both the lease and the loan. For the down payment, we'll assume the buyer puts down $1,800 to cover six percent sales tax, which, unlike with a lease, must be paid up front. We'll assume the lessee contributes the cost of two $695 acquisition fees.

Now let's compare the three major costs: the principal, interest and state sales tax.

Principal: As I explained earlier, the lessee's monthly payments will be based on paying back $15,000, compared to $30,000 for the purchaser. But remember, the lessee is leasing twice. This means that by the end of the second lease, the lessee will have paid back the same $30,000 as the motorist who bought the car. Now, here comes the big difference: After returning the vehicle after the second lease, the lessee has nothing. In contrast, after paying off the six-year loan, the buyer still will have a car worth around $10,000, if not more, for a net cost of $20,000. And that $10,000 difference will be even greater if the vehicle price has increased by the second lease.

Interest: Because of that higher unpaid monthly balance under the lease, the lessee ends up paying $2,025 more interest than the purchaser over the same six years. And it gets even worse if interest rates have increased when it comes time to lease again, a good bet given that rates have been on the rise. Even if the lease and loan rates were just one percent, the lessee still would pay $675 more. (The interest charges would be less if either motorist made a larger down payment, but that wouldn't affect the $10,000 difference in the principal payments.)

State sales tax: Instead of taxing the entire cost of the car, as with a purchase, most states tax only the monthly lease payments. That results in a huge tax advantage for the lessee. For example, in our comparison, the buyer would pay tax on $30,000, while the lessee is taxed on just $15,000 plus the $1,022 interest. But since the lessee is leasing twice during those six years, he's taxed twice, too, leaving him paying more tax than the motorist who bought the vehicle. In other words, when you lease twice compared to simply buying and holding onto the car, you're effectively giving back the sales tax break you got during the first lease and then some.

Adding things up

When you add to all this the two lease acquisition fees totaling at least $1,190, the net cost for the lessee is nearly $13,000 higher than for the buyer. And the amount would be even higher if the lessee is charged additional fees for causing damage or other so-called excessive wear and tear to the car or for driving more than the allowed number of miles. Some leases limit lessees to just 10,000 miles annually, charging the lessee 10 to 25 cents for every mile over the limit. The purpose is to compensate the leasing company for greater-than-expected depreciation. But the actual loss in value is likely to be far less than the fee.

For example, Kelley Blue Book reports that the trade-in value for a three-year-old Toyota Camry declines by around five cents for every mile driven over 30,000 miles. Conversely, if you return the leased vehicle having driven less than the allowed number of miles, you will have paid for depreciation you didn't use.

One thing I haven't factored in is the amount the lessee would save in maintenance and repair costs by always having two relatively new cars, both covered by the manufacturer's bumper-to-bumper warranty, which typically lasts three to four years. In contrast, the buyer will go two to three years without comprehensive coverage. Still, the purchased vehicle will likely be covered by the manufacturer's more limited power train warranty, which usually lasts six years, but with some carmakers can be as long as a decade.

But even if the car buyer incurs some repair and maintenance charges the lessee avoids – such as a new battery, brake pads and set of tires, they're unlikely to cost anywhere near the more than $12,000 the purchaser saves, especially if the car is a reliable model that's well-maintained. And when it comes to maintenance, car owners can save a lot by skipping those pricey repair shop maintenance packages.

When leasing might pay off

There may be some instances in which leasing might be the better financial choice. One example is if a carmaker is offering incentives to lease customers without providing an equally valuable package of rebates or low-interest financing to buyers. Another example is if your plan is to buy a vehicle using a long-term loan but to trade it in within the first couple of years or so. In that case, you will have paid back so little of the loan that leasing could be a less or equally expensive alternative. But in either of these cases, figuring out whether a lease or loan is less costly is extremely difficult.

If you always want to drive a new car

You may have read that leasing makes sense if you want a new car every few years. But even then, there's a better way. Instead of leasing, buy the first car using as short a loan as you can afford. Then, once you've paid off all or most of the loan, trade in or sell the vehicle and roll the amount you get into the down payment on the new car. That will reduce the size of your next loan and leave you with a low lease-like payment without all the lease-related headaches. But even then, you'll end up paying thousands more than if you just kept one vehicle for the long term.

What to do

If money's no object, leasing may be for you. You can get a new car every few years without worrying about trading it in or selling it on your own.

But that's not the case for most people. For many, leasing is a way of getting a new car they otherwise couldn't afford because their income is too low and they have little or no savings. As a result, many lessees, already financially stressed, end up choosing the most expensive way of acquiring a vehicle, one that laving them making unending monthly car payments.

If that's you, forget the lease and consider buying a car instead. The best way is to save your money and pay cash. But if you can't do that, choose a vehicle that you can comfortably afford while still covering your other expenses and putting away some savings. The rule of thumb is to choose a car that you can afford with a loan of no more than 48 months and to make sure you can make at least a 20 percent down payment. Depending on your finances, that may mean having to settle for a used vehicle. If you need to lease or take out a long-term loan with little down payment, you're opting for more car than you can afford.

Should You Get a Mortgage Online?

Mortgage websites are increasingly popular and great resource. But they're not the only way to go

4/26/19

You're likely seeing a lot of advertisements these days from online mortgage lenders who want you to think that getting a mortgage on the web is quick and easy.

So when researching or applying for a mortgage or mortgage refinancing, should you forget the trip to your local banks, credit unions and other walk-in lenders?

As enticing as these ads may seem, the answer is: probably not.

It's fine to begin researching a mortgage online. And ultimately you may decide that's where you should get your loan. But don’t expect it to be as simple and fast as some of those advertisements imply. And you may be able to find better deals elsewhere.

Online mortgages gain in popularity

Shopping for a mortgage online is becoming increasingly popular. In its 2017 mortgage satisfaction study, J.D. Power reported that, for the first time, mortgage shoppers submitted their applications online more often than any other way, including by visiting a walk-in lender. But in its 2018 study, it found that only 3 percent of mortgage customers used mortgage self-service tools exclusively. And that’s probably for the good.

Shopping for a mortgage or refinancing can be complicated, especially if you're new at it. It's often helpful having a real-life human to explain the process and answer questions in person. Also, rates from online lenders aren't necessarily better than you can get locally. So it makes sense to cast a wide net. Finally, even if you get a mortgage online, don't expect to avoid paying those pesky mortgage-related fees, which typically amount to thousands of dollars.

Consider starting online

One of the things mortgage websites have in their favor is that they typically provide a lot of easily accessible information about how mortgages work, which can be very helpful if you're just starting out. Some websites also have handy mortgage calculators. At three of the sites I checked, Better Mortgage, Lenda and First Internet Bank, I was able to obtain customized mortgage estimates, including rates, closing costs and other fees, such as those borrowers have to pay for an appraisal, credit report and title insurance.

All I had to do was enter a few details, including the zip code and cost of the house I was planning to buy, the amount of my down payment, the length of the loan and my credit score. I was able to adjust the estimates by changing the various criteria. That's handy if you want to test different scenarios, such as how making upfront payments, known as points, might lower your estimated rate. In none of the cases did I have to submit an application or provide personally-identifying information. That’s good because applying requires you to lift any credit freezes you've put in place and provide a lot of sensitive information, such as your date of birth and Social Security number. And applying for a mortgage can temporarily ding your credit score, an unnecessary step if you're only trying to get a feel for where you stand.

But not every website I checked was as convenient. At SoFi Lending Corp, I couldn't get a customized estimate without registering and providing personal information, including my name, email address, and date of birth.

And the largest and perhaps best known online lender, Quicken Loans' Rocket Mortgage, wouldn't provide an estimate unless I actually applied. Also, while those Rocket Mortgage ads say you can get approved for a mortgage in as little as eight minutes, don’t expect your printer to spit out a check by the time you close your computer browser. What the lender actually provides is what the industry calls a pre-approval, which still can leave you a month or so from actually getting your mortgage. One upside of the Rocket Mortgage approach is that rates quoted based on a pre-approval are likely to be more accurate than those you'd get without actually applying. And Rocket Mortgage, like some other mortgage websites, lets you conveniently upload documents the lender will require, such as proof of income and employment.

What to do

If you don't know how mortgages work, start by looking at some independent sources of information, such as the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Trade Commission. Also, check the useful information on mortgage websites. While you're at it, try to get at least a primarily estimate of the deals you'd be eligible for. But don't stop there. Also check with local banks, credit unions and other walk-in lenders. Also check at least one mortgage broker, advises David Reiss, a professor specializing in real estate financing at Brooklyn Law School. Reiss also is editor of the real estate finance blog REFinBlog.

Keep in mind that mortgage rates can change quickly. So try to find as many rates as you can without a day or two to be sure you're making a correct comparison. To get the most accurate rates, you'll need to formally apply. The first application will ding your credit score, but the others won't as long as they're within 45 days of your first one. Also keep in mind that rates can change between the time you apply and the mortgage is issued. So one you're pre-approved, find out a what point you can lock in your rate.

Before moving forward with a mortgage or refinancing, check out the lender’s reputation by looking for a company report at the Better Business Bureau. Also, try a web search with the lender’s name and such terms as “reviews” and "complaints" to see what others are saying. That not only can tell you something about how well the company treats its customers, it can give you an idea of the issues people encounter and the questions you might ask up front. For a mortgage website, one thing to look for is how easy it is to contact a representative by phone if you need to speak with someone. Finally, you can verify whether a lender is licensed to operate in your state by visiting the Nationwide Mortgage Licensing System.